Mia A. Mottley, Prime Minister, Barbados

I stand here clothed in the spirit of the battles of Adwa, conscious that it was that battle, fought within 24 hours, that shook the confidence of the powers of Europe but inspired the people of Africa and the children of the African diaspora. It taught us that good would prevail over evil and light over darkness, but only in the context of our unity. I stand here, conscious that it was that battle that forged the beginnings of Pan-Africanism and eventually led to the movement for independence, dismantling the colonial powers. This did not grant us full development and power, but it gave us the first steps towards political independence.

I stand here, guided by the dreams and works of the great Pan-African pioneers, and conscious that as children of the Caribbean, we have long yearned for unity with our brothers and sisters of Africa. A division that was enforced by those whose success and survival depended on our separation, rather than on our ability to act as one common people. Our relationship, you could say, was embryonic, but regrettably, as long-standing and as deeply connected as we have been, it has remained sporadic. It is up to us, as children of independent states, to determine whether the history of separation will be our future or whether the spirit of Adwa can inspire us to confront the challenges of a new world.

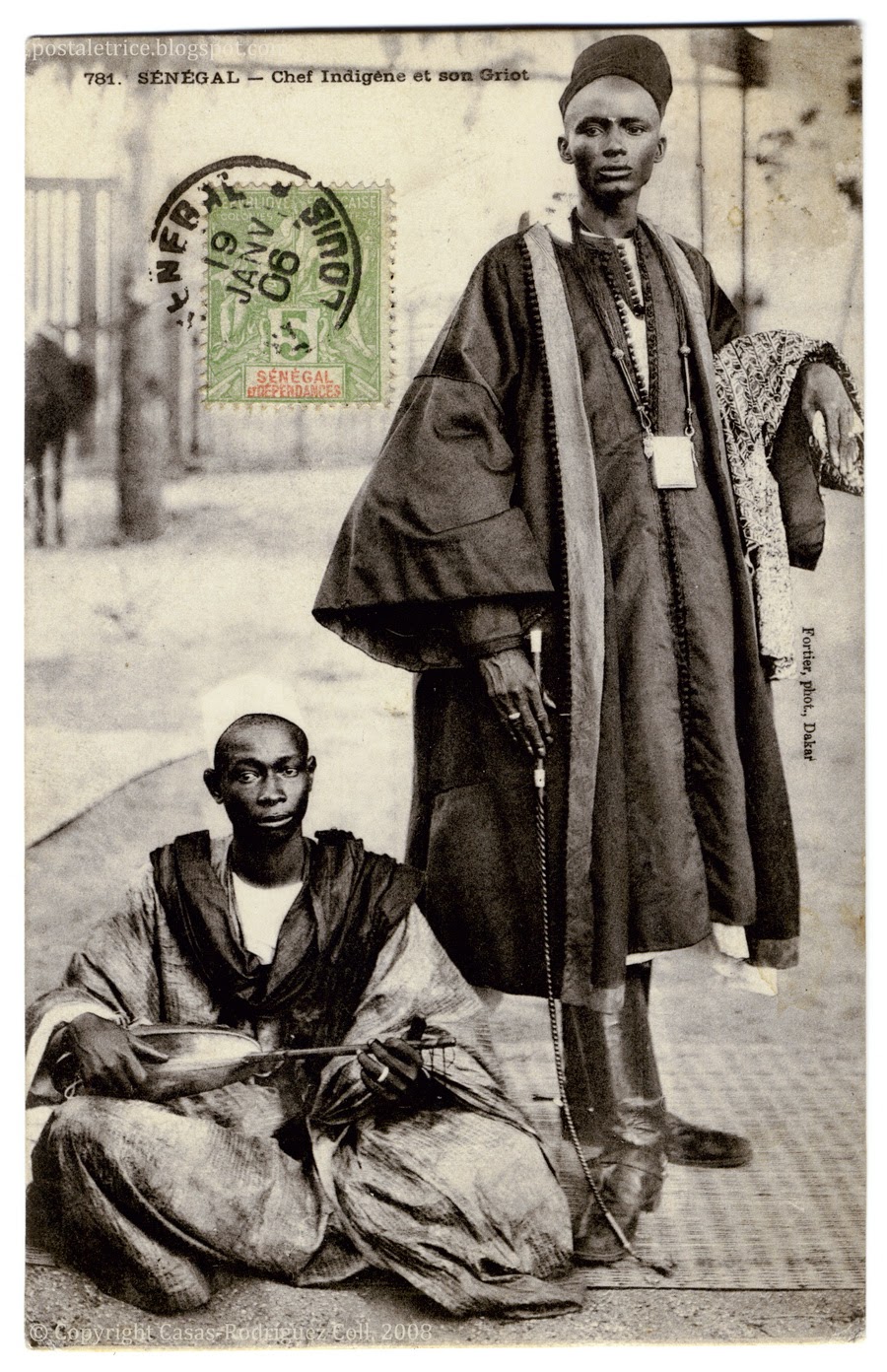

Yes, I stand here as a daughter of Africa. I also stand here as the proud Prime Minister of Barbados, a country that is the first landmass one reaches after leaving this great continent of Africa. A country that, in the past, became a hub for the wrong reasons but, today, I come to Ethiopia and the African Union to share with you that we can now be a hub for the right reasons—bringing our two peoples together. I stand here as the proud Chairman of CARICOM, the Caribbean Community, recognizing that as members of the Sixth Region of Africa, we have come to reclaim our Atlantic destiny. We have come to ensure that the very future of our people is different, and will no longer be determined by intermediaries who used the Middle Passage to see our people at the bottom of the ocean floor of the Atlantic or toiling in the fields of the plantations of the Caribbean. Instead, we must forge a future where our people are seen, heard, and felt, ensuring that we determine how we cooperate, integrate, and invest, rather than remain victims of a past history.

I stand here also as the Chair of the V20, a coalition of 70 climate-vulnerable countries, 40% of which come from this great continent of Africa. I recognize that it is only through unity that we can confront the existential crisis of our generation—the climate crisis. The Secretary-General of the United Nations has already laid out, quite ably, the many inequities we continue to face despite political independence. It was His Majesty Haile Selassie who reminded us that there shall be no first-class or second-class citizens, words later popularized by Bob Marley. These words, learned by our people, should be understood within the context in which they were spoken and the mission they set for us. His Majesty warned us that there would be war if people were treated as first-class and second-class citizens, and if the color of our skin was considered more significant than the color of our eyes.

Today, we see conflicts on the continent born out of ethnic divisions, out of a desperate grab for resources—often not for our own benefit, but for others who seek to use our people as pawns in securing their future. Yet, we stand here as proud people, fully capable of distinguishing right from wrong and forging a future that benefits the many, not just the few. As the world faces the climate crisis, it is the poorest of the poor who remain most vulnerable to floods, droughts, and hurricanes. Soon, even the middle class will no longer be able to access insurance, hindering their ability to rebuild and develop unless we make urgent changes.

We have seen partnerships work for us, not just through the spirit of Adwa and the rise of the Pan-Africanist movement, but also in recent times. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was the African Union, under the leadership of President Ramaphosa and with the assistance of Dr. Tedros of the WHO, that ensured the Caribbean was not marginalized. Through the Africa Medical Supplies Platform, we gained access to essential therapeutics, medical equipment, and vaccines. Likewise, through the solidarity of many of you in the African Union, the Bridgetown Initiative took root, advocating for a more just and modern financial system that allows us to pause debt repayment during crises, ensuring our ability to rebuild after climate disasters.

We do not need more evidence that partnership works. What is required of us now is leadership—towards peace, prosperity, and justice. And when we call for reparations from the international community, we first ask for something simple: an apology. A sincere acknowledgment of wrongdoing. But beyond that, reparations must also ensure fair access to development and compensation, because our journey to independence started with a chronic deficit—a deficit of resources, fairness, and opportunity. It is up to us, the second and third generations of independence, to frame what reparations must look like in a mature and constructive conversation, ensuring justice for our people and inspiring the youth to believe that good must always triumph over evil.

Yet, it is not only the international community that must act. We, too, must repair the damage imposed upon us. The fact that our people must beg for transit visas to move across the world is unacceptable. To travel east or west, we are forced to go north. This is not right. It is within the power of African and Caribbean leaders to change this, to build air and sea bridges that guarantee we control our own destiny. Let us make these changes, not just for heads of state, but for ordinary people who wish to trade, travel, and forge a shared future.

As artificial intelligence threatens to reshape humanity, we must not again be left as victims of technology, as we were with gunpowder and industrialization. We must shape the future, for Africa has always been a humanizing force in civilization. How can a continent that holds 40% of the world’s minerals not be at the forefront of securing the planet’s stability? How can a region that represents a third of the world's nations not act with singular purpose to redefine global governance?

My friends, we must secure this victory. By 2050, one in every four people on the planet will be from this continent or its diaspora. Our leaders have a moral imperative to ensure unity. The spirit of Adwa demands that we recognize our potential, that we act in unity despite the forces that seek to divide us. If we fail to achieve this unity, the fault lies not outside, but within.

Some may call this the dream of a naive and romantic daughter of Africa. But if that is the case, I would rather be naive and hopeful than cynical and paralyzed by the power of others. Our history proves that unity is possible. We fought apartheid together. We liberated southern Africa together. And today, we must forge a new path together.

As we prepare for the first in-person CARICOM-Africa Union Summit in Addis Ababa this September, let us seize this moment to solidify our partnership. In Barbados, we will host the 15th Caribbean Festival of Arts (CARIFESTA) this August, inviting our African family to celebrate our shared culture, food, music, and philosophy. This is our opportunity to show the world that we are not mere footnotes in history, but central to shaping the future.

Let us remove the scars of history and build the future our people deserve. We must emancipate ourselves from mental slavery and fulfill the promise of Adwa.

Thank you. [Applause]